top of page

water water

This work is supported in part by a grant from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, through an appropriation by the Rhode Island General Assembly and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Artist Statement

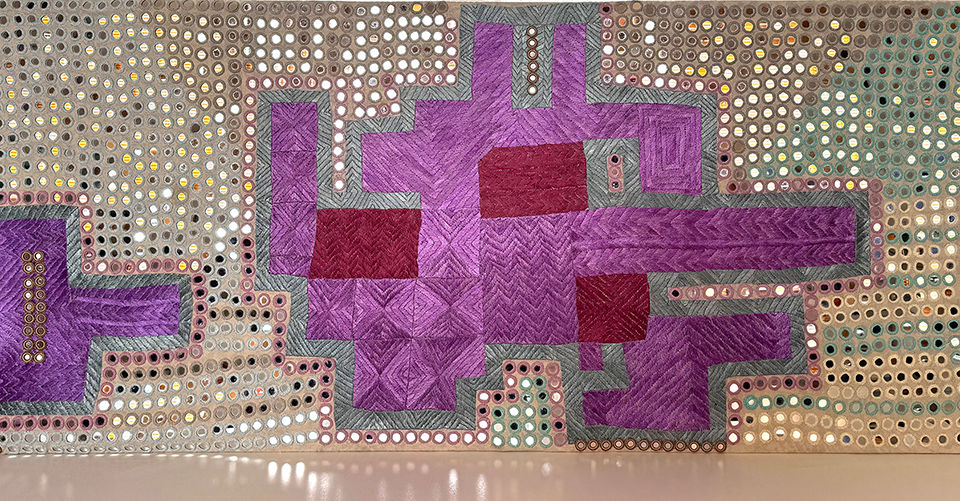

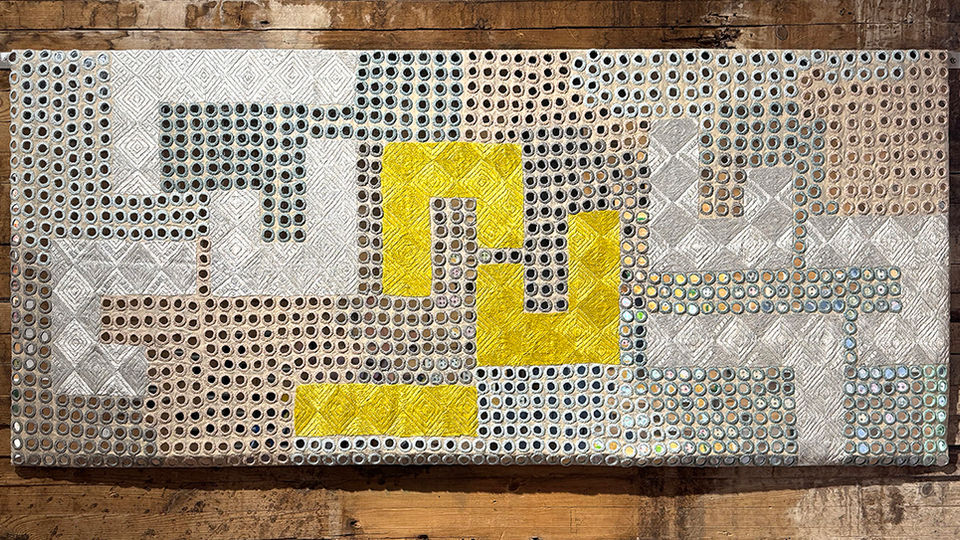

In a fluid compendium of formative years and later life experiences, I anchor my work in cross-cultural spaces addressing heritage, fractured lineages and socio-environmental injustices. I am passionate about textiles in both ceremonial and everyday use. Re-using, preserving family textiles has been a generational practice. Pakistan and India’s 1947 partition severed these traditions by splitting cultural connections. Collapsing time between contemporaneity and cultural inheritance, I stitch, mold, assemble textiles to symbolically reconstruct our divided family. Dyeing, embroidering or engineering flat fabric into luminous, ethereal, architectural or biomorphic forms, I create luminosity and material reflectivity to garner self-reflection, identity, possibility and change. Through physical, and metaphysical material luminescence, I transition the joy of light into the joy of life. With empathy as a catalyst of understanding, I promote calm amidst chaos, serenity and hope amidst loss and destruction.

Humans are drawn to material shine, glitter and reflections. Walk into Lahore Fort’s Shish Mahal’s elaborate mirror patterns dancing in lamplight, or fly over golden sunlight on water, the joy of light and reflections stay with you forever. Even if it is flood water that has wreaked havoc on life and property, the golden light still spells hope.

First mirrors in human use were bodies of still-water. Earliest mirror, found in Anatolia, dates back 8,000 years, followed by 4,000-year-old pieces from Egypt and Mesopotamia. These regions traded with Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus River Valley, but little is known about the dissipation of Mohenjo-Daro’s population. Are Banjara and Rabari nomads, with their rich history of shisha-work, off-shoots of that civilization? Did they spread the craft to 13th century Persia from where it came back to the Indo-Pak sub-continent via the Mughals, refined, redefined from folk to court, by the 17th century? Prevalence of mirror embroidery around Pakistan’s great rivers is perhaps an evolutionary, embedded memory of light and reflections on water that intuitively led me to use shisha-work for showing aerial views of Pakistan’s catastrophic 2022 floods.

During architect Yasmin Lari’s 2022 post-flood housing reconstruction in Sindh, scarcity of embroidery materials led women to decorate facades and hearths with mirrors. Could movable, interchangeable architectural shisha-work screens capture or deflect solar heat as needed, or illuminate non-electrified rural settlements? Agricultural predators stay away from shining detractors; could shisha work covered poles keep birds at bay?

Human evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich posits that cross-generational, cross-communal sharing of knowledge brings about creative brilliance. I seek this knowledge through inherited textiles, in embroidery commonalities from Baluchistan to Palestine as documented in the soon to be published Volume V of Naheed Jafri’s Balochistan Nama, or in Nasreen Askari’s textile collection recently installed at the Haveli Museum in Karachi. Addressing time not as linear, but dimensional continuum, I feel connected to communities of women, who have sustained and enriched lives through the ages with the magic and innovation of needle and thread.

bottom of page